Category: Articles

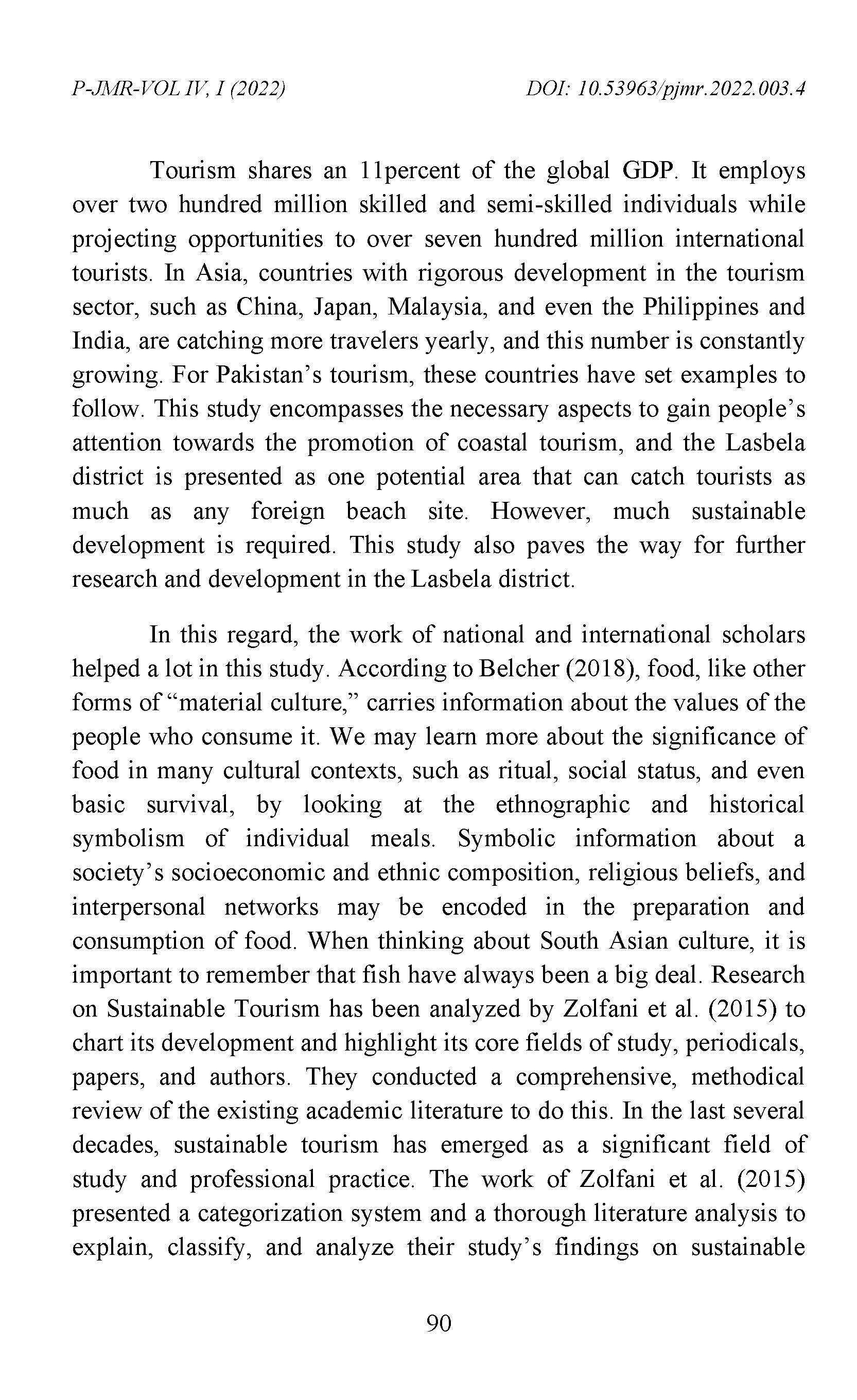

State of Microplastics in the Marine Environment, Existing Trends, and Future Perspectives.

Effectiveness of Revised Merchant Marine Policy and Long-Term Financing for Shipping Sector in Pakistan

Kanwar Muhammad Javed Iqbal

V/Adm (R) Abdul Aleem HI (M)

Sadia Abdullah and Fida Hussain

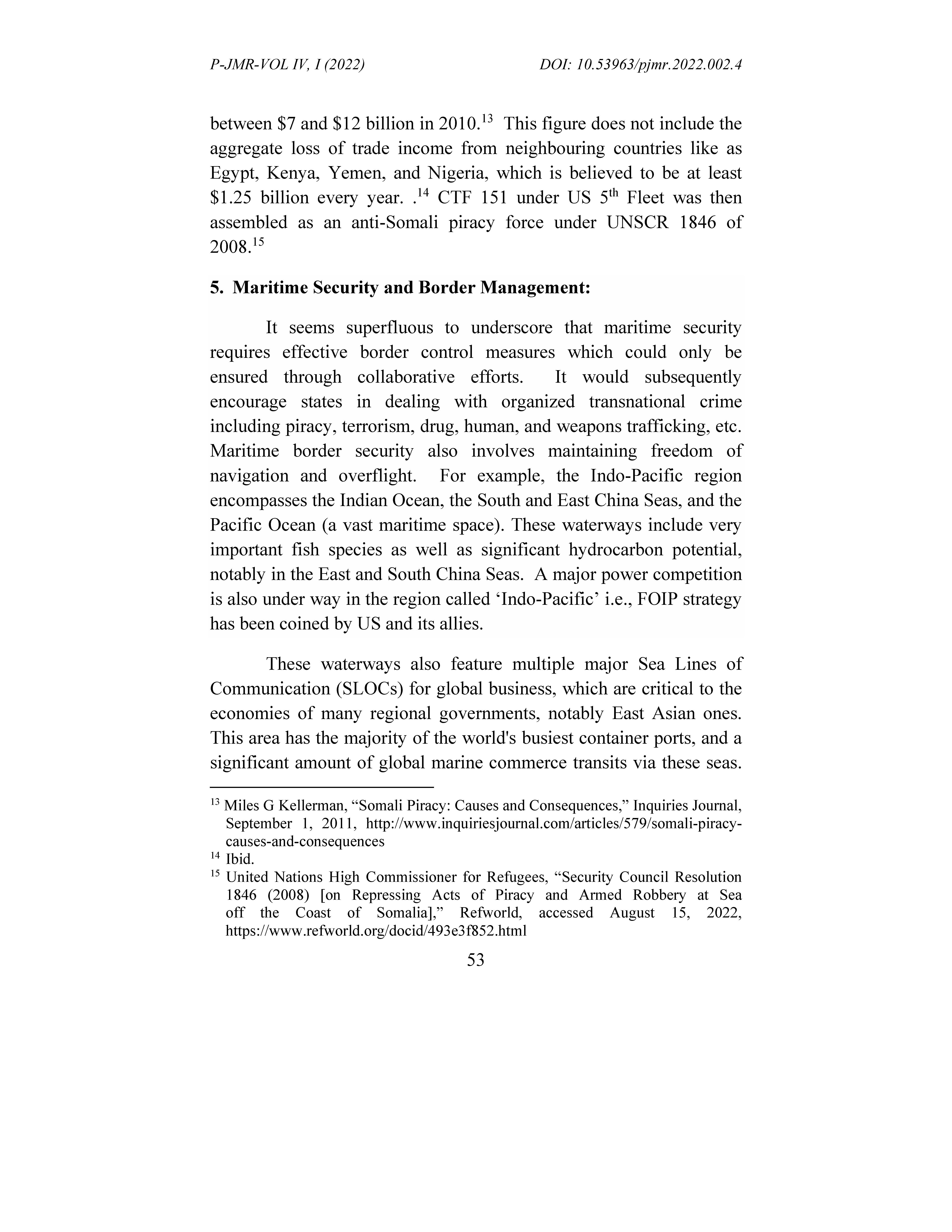

ABSTRACT

In the contemporary globalized world, a strong national shipping sector and healthy state of national flag carriers is the reflection of a thriving economy. In case of Pakistan, unfortunately, the number of national flag carrier is just 11 ships; whereas, the contribution of private entrepreneurs is almost nil. There is an enormous growth potential for shipping industry in Pakistan which needs to be harnessed through enabling policies, processes and regulatory framework. In this context, Pakistan Merchant Marine Policy (MMP) 2001 was formed which was amended by the Federal Government in November 2019, extended till the year 2030 and launched in July 2020. Moreover, the State Bank of Pakistan (SBP) has issued the rules for ship financing under Long Term Financing Facility (LTFF) in July 2020. A question arises regarding the effectiveness of MMP and financing instruments. This study has examined the revised MMP 2001 document and the SBP’s LTFF for the Shipping Sector, by employing qualitative method. Based on analysis, this study has identified that the existing policy and legal framework has several issues due to which active engagement of private sector couldn’t be achieved and always remained a big challenge for shipping sector of Pakistan. MMP 2001 is fragile as it lacks the legal status enjoyed by an act of the parliament / ordinance and the provisions are subject to the Cabinet / ECC decisions made from time to time. Capacity gap is also among key challenges at the level of MoMA to address shortcomings in policy and legal framework through meaningful consultation with stakeholders. Channeling of finance through MoMA causes procedural delay while MMP does not promote ease of doing business for private investors. However, the documents are beyond the capacity of being amended and need to be drafted afresh including; MSO 2001, MMP and LTFF. It also argues to have an active role of a think tank or an academic institution to assist MoMA on long-term basis.

Keywords:

Merchant Marine, Revised Policy, Shipping Sector, Long-term Financing, Private Investors, National Flag Carrier

Causality Analysis between Poverty and Environment: A case Study of Pakistan’s Coastal Belt

Russia’s permanent military presence in the Syrian Tartus port for the coming 49 years: Increasing maritime security challenges in the region

NON-TRADITIONAL SECURITY THREATS IN MARITIME ZONES OF PAKISTAN AND LAW ENFORCEMENT BY PMSA: AN OVERVIEW

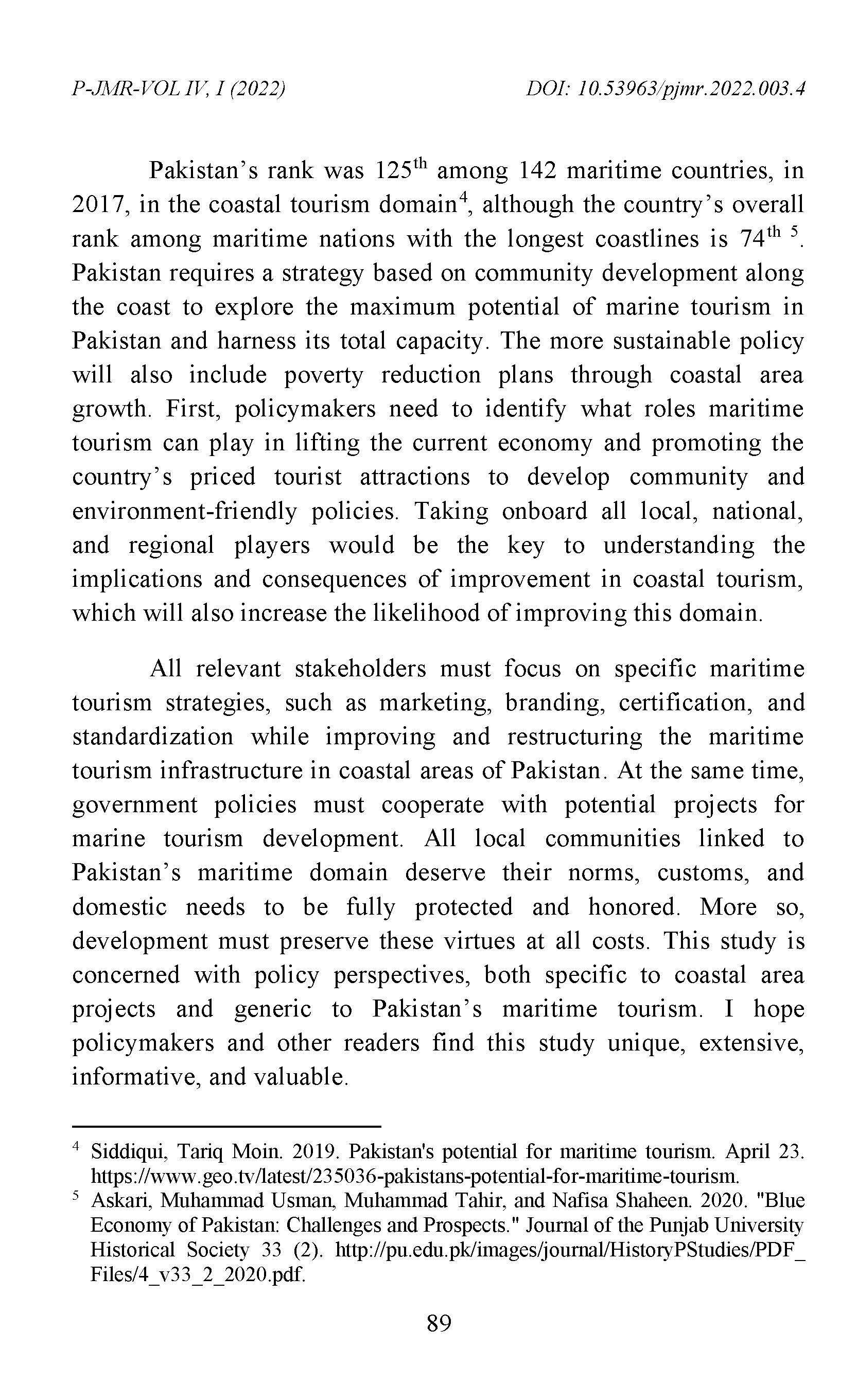

Maritime Tourism Potential of Lasbela District (Pakistan): The Course of Sustainability

MARITIME BORDER MANAGEMENT AND CHALLENGES IN WESTERN INDIAN OCEAN (WIO)

Maritime Security Dynamics of Archipelagic States: The Case of Maldives

Abdul Lateef Ali,

Naghmana Zafar

Abstract

Maldives is an archipelagic state situated in the birth place of maritime civilization- the Indian Ocean. In recent years, Maldives has seen a growing attraction towards its maritime space with the expanding economy fuelled by growing international tourism, shipping, overseas trade and fisheries. Owing to the strategic position of the country and its proximity to vital Sea Line of Communication (SLOC) that are infested with rising threats and crimes. Though Maldives does not have any territorial disputes with neighboring countries, the country is facing great challenges in dealing with narcotics, ERF and other non- traditional maritime threats especially environmental challenges. Maldives is facing various threats for her existence other than the issues faced due to climate changes. In order to meet these challenges it is proposed in this paper, the re-conceptualizing of Maldivian maritime management. An umbrella organization of Maritime Authority is proposed to synchronize the operations and information gathering of the Marine Police, Customs Services and Immigration department. Increased regional cooperation is proposed in order to tackle the collective non-traditional maritime security threats faced by the region as a whole. This paper does an extensive comparative analysis of the practices held in the regional and other archipelagic countries to draw lessons for Maldivian case study.

Keywords: Indian Ocean, Archipelagic State, Non-traditional Security, Maritime Threats

* Major Abdul Lateef Ali is in Maldives National Defense Force, Republic of Maldives. He is also an alumnus of Pakistan Navy War College.

** Naghmana Zafar is Senior Researcher at National Institute of Maritime Affairs (NIMA).

1. Maritime Character of Maldives and Scope of the Study

Characterized by its surrounding vast seas, Maldives is a coastal state situation in the birthplace of the Maritime Civilization – the Indian Ocean. The very reason of its birth and evolution as a nation was seen through its important geographic position when sailors and traders who traversed the Indian Ocean stopped their vessels in these islands to take refuge from adverse weather conditions, where this eventually led to the settlement of its earliest inhabitants. Maldives was formed up by two chains of disconnected tiny islands, placed in north-south direction, the ocean is where all of its security and economic interests lie, either within or interlinked.1 Marine resources are the country’s main natural endowments and the seas are its climate regulator, transport route, and trade route of the nation. The reliance on the seas for sustenance and security defines the country’s maritime identity.

This research work is intended to study and critically analyses only non-traditional maritime security threats and risks in the Indian Ocean which are detrimental to the security and future of Maldives. The research will not address traditional threats, and therefore security issues arising from political or military rivalry in the region are out of the scope of this research paper. Due to the ongoing restructuring of the country’s Defence forces, this research becomes quite pertinent to provide essential policy recommendation for the new Defence doctrine to cope up with the emerging challenges to the maritime security of the country. For the purpose of this research a qualitative research study is conducted. Qualitative research compared to quantitative research

2. Threat Infestation and Maldives’ Concern

The world has witnessed an evolving strategic environment in the IOR post- Cold War. The shift of focus from a Euro-Atlantic to the

1 “Maldives History – Early Settlers, Conversion to Islam, Maldivian Heroes, The British Protectorate, Independence”. Accessed 12 October 2019. http://www.vermillionmaldives.com/maldives-history.htm.

Indo-Pacific region and repositioning of global economic and military power in the Asian continent has resulted in significant political, economic and social changes in the Indian Ocean Region. Some of the drawbacks of this shift of global focus towards the Indian Ocean are seen in the form of evolving and increasing maritime threats. Maldives, as a small nation maintaining its non-aligned status in the world politics would not be directly affected by the power struggle among regional and extra-regional powers in the Indian Ocean. In other words, the real adversary of Maldives in the maritime domain is non-traditional maritime threats resulting from the changing geo- strategic environment.

Maldives is in dire need of modern approaches to maritime security, especially at this particular juncture of history as Maldives has embarked upon new economic ambitions with future development plans which are hinged to the maritime environment. Suppression of maritime threats and closing the threat gaps is absolutely essential for the success of these national aspirations and ensuring national security. It is believed to be more challenging for any nation to guarantee its territorial integrity, prosper and expand in the future, without appropriate measures against growing threats and challenges at sea. The transnational nature of these threats pose a great challenge to the countries across the region, and more so to small coastal countries like Maldives.

3. Non-traditional Threats for Maldives

According to various studies the non- traditional maritime threats to any archipelagic state are divided into three categories:

i. Threats due to natural phenomena which includes, wave and tidal surge, Coastal erosion, flooding due to monsoon rain, extreme high winds threatening the vegetation and infrastructure and effects of climate change and sea level rise, including coral bleaching. Further he highlighted that these threats basically challenged physical existence of an island and therefore makes people to migrate for safer places causing other socio economic

ii. Threats nefarious criminal activities and threats of non-state actors. These threats include religious extremism, radical cults, drug trafficking, illegal fisheries, environmental pollution, Sabotage to National

iii. Impact of geo-strategic equation of Indian Ocean and Maldives Government’s or Institution’s involvement in the great powers rivalry. This could lead to potential militarization of Maldives and attract unwanted and unnecessary attention, making Maldives more

a. Piracy: This is a phenomenon which has evolved over the centuries and millions of dollars have been spent by the maritime community to overcome this challenge. Piracy for archipelagic states is a challenging threat to tackle as pirates can utilize multiple fronts to maintain an element of surprise. The overall security of maritime traffic throughout the region is a key strategic priority, for nations in and outside the IOR. The threat of piracy currently seems to be mainly around waters between the Red Sea and the Indian subcontinent and the South-East Asia.2 Straits of Malacca and Singapore are highly infested, International Maritime Bureau (IMB) has given multiple cautionary notices to the travelers and merchant ships to remain vigilant when travelling through South East Asia and Indian sub-continent even in February 3

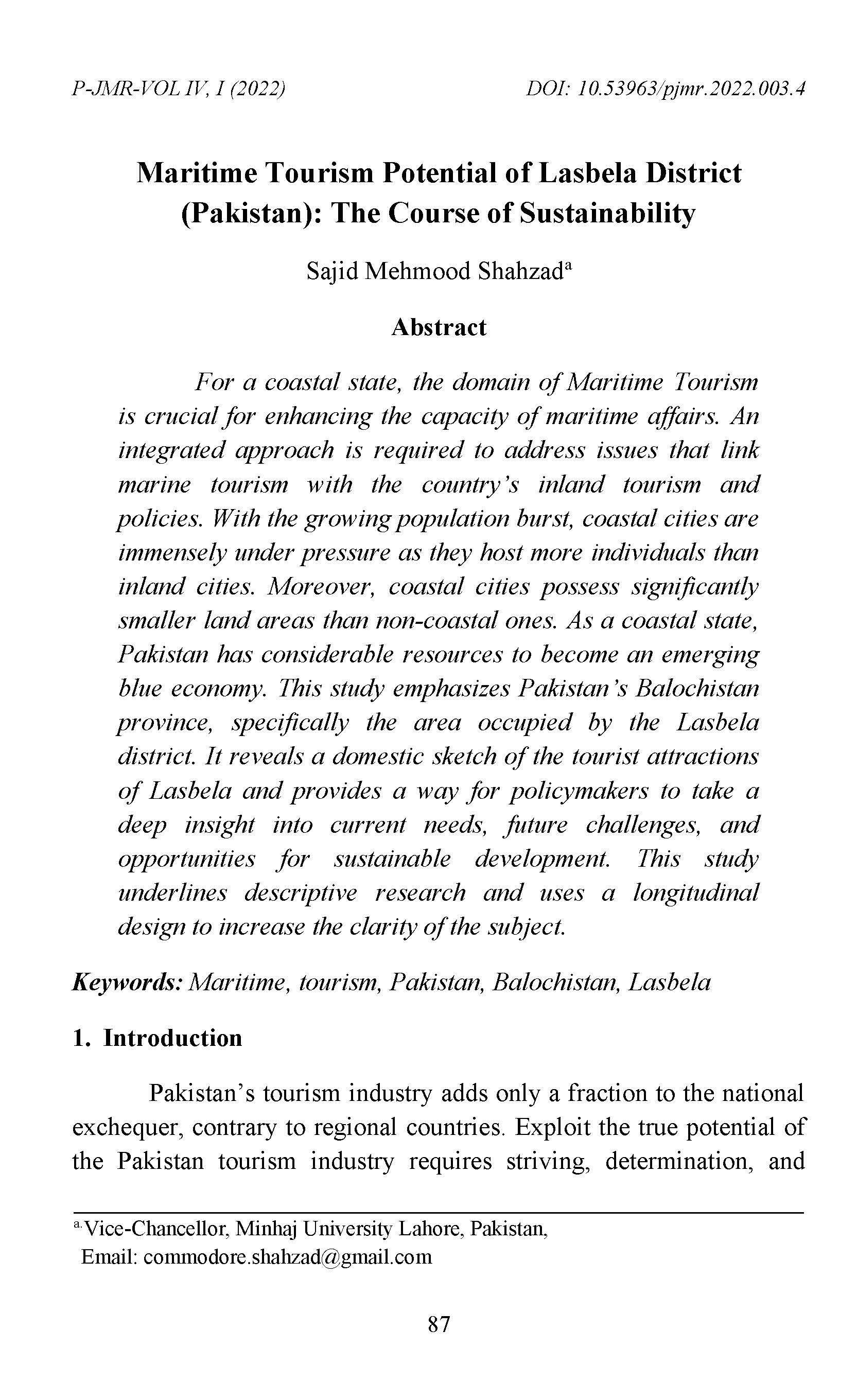

Figure 1: International Maritime Bureau live piracy map

Source: IMB live piracy map (https://www.icc- ccs.org/index.php/piracy-reporting-centre/live-piracy-map)

There has been no case of piracy reported since 2011 in and around Maldives. However, there were 42 Somalis apprehended in different incidents between 2009 and 2011, found in small skiffs within the littorals of the Maldives. All the apprehended Somalis were handed over to International Committee of the Red Cross in 2014.4 Another foreseeable threat related to piracy is a huge large community of fishermen remain within the EEZ of Maldives with small fishing vessels with limited communication facilities yet they tend to approach the foreign vessels around their vicinity. These activities are a major source of concern as these activities can be mistaken as an act of piracy, which may result into legal action against them as well as it is liliikely that they may face life threatening consequences.

b. Maritime Terrorism: In the history of Maldives many incidents of maritime related terrorism have been witnessed due to the weakness in terms of maritime security and easy accessibility of the sea route to the terrorist organizations. In December 1752, Malabar (a group belongs to Indian Territory between Karnataka and Kerala) invaded Maldives through the sea route and ruled the country till 7thy April 1753, which is a classic example of how vulnerable Maldives is to maritime terrorism.i This was the situation till 1st January 1981 when Maldives then President Maumoon Abdul Gayyoom officially introduced maritime security component, Coast Guard. Though maritime security force is established, due to the lack of concern among the security forces, 3rd November 1988 terrorist attack took place through sea which resulted into the death 19 Maldivians, including 11 casualties of security forces. Such incidents increased the importance of change in the approach of security paradigm. Significant improvements in maritime security – particularly MNDF CG – has been observed Nevertheless, due to the geographic location and the nature of formation of atollsand islands it is agreed that monitoring of all the boundaries of Maldives is still afar-fetched The fragile state of maritime security was observed when former Vice president of Maldives escaped his trial by leaving the country on a cargo vessel.

c. Illegal Unregulated and Unreported (IUU) Fishing: Illegal, Unreported and Unregulated (IUU) fishing is a term which covers various activities involves in fishing. IUU fishing can be observed within the territorial waters and beyond. IUU fishing is a big challenge for the maritime nations where large population depends on the financial benefits from the fishing industry as well as their daily meal is based on seafood. IUU fishing goes against the rules, enacted to manage and conserve the marine life and as a result it effects the long-term sustainability of marine resources in the respective country or the

Furthermore, IUU fishing violates the rights of those fishers who obey and follow the regulations and act responsibly.5

IUU fishing is a prominent threat in the Indian Ocean, especially in the important tuna-rich waters of Seychelles, Madagascar, Mauritius Comoros and Maldives. Overfishing and depletion of certain fish stocks and species in the Indian Ocean are impacting food security in a broader sense with added loss of economic benefits to countries like Maldives dependent on fisheries and marine resources. World fishing fleets are moving towards the Indian Ocean due to the depleting marine resources in other parts of the world and the increased global demand for fish. Every year, the region loses $2bn worth of fish to illegal fishing, and apart from depriving the region of revenue, overfishing reduces fish stocks, reduces the share of local fishermen and harms the marine environment.6

The mission of Maldives fisheries sector is “to strengthen the fisheries sectorin order to increase its competitiveness and sustainably manage all marine living resources in the maritime zones of the Maldives” and the vision is “to transform the fisheries and agriculture sectors into a sustainably managed and market-oriented system that contribute to socio-economic growth, food security and sustainable management of natural resources”.7 To achieve these objectives Maldives fisheries regulation says that allows fishing other than net fishing.

d. Climate Change: The Indian Ocean is considered one of the most productive oceans and has witnessed global warming at a rate of 1.8 degree Celsius over the last century which is very high and sea level raising compared to global surface warming up to 0.8 degree Celsius during the same period. 10Small Island States are at forefront of climate change impact. Inter-governmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) report warns the low lying small states that global temperature are likely to increase by 1.5 degrees between the year 2030 and 2052.11 Due to the unique geographical features, including coral landscape of over one thousand and two hundred, in the context of climate change Maldives is considered one of the island nations most likely to be vulnerable to impact due to global

These small low lying islands are constantly at risk of coastline erosion and storm tidal waves. Growing pressure to the coral reef due to human development and rising temperature of both, water and air, cause imbalance on the ecosystems. Maldives is going to face extreme weather patterns, such as extensive precipitation and storms. Maldives vulnerability to climate change has been awakened especially after tsunami resulting from the Indian Ocean earthquake, which hit the island in 2004.ii As a result, the National Disaster Management Centre (NDMC) was established, but risk management and adaptation policies developed, especially on the community level are still inefficient.

Figure 2: Erosion of Island

Source: a Local from Raa Atoll Kinolhas, January 2020

e. Maritime Pollution: Major accidents arising from oil bunkering, shipwrecks and collisions at sea can have serious consequences to the marine environment. Oil pollution can be regarded as an inevitable outcome of the dependence of a rapidly growing world community on oil-based technology. Apart from this, deliberate discharge of harmful quantities of oil and other hazardous substances, garbage, cargo residues, ballast water and sewage renders severe environmental damage to the ecosystems and even impact economies of the countries. Maldives is a country where economy is dependent on tourism, clear lagoons, underwater beauty and sandy beaches are reasons tourists travel from all over the world. Oceanic damage such as oil pollution would have detrimental effects on thecountry’s

f. Drug Trafficking: The country is a small archipelagic state combined of 100% Muslim nation, however influenced by many external illegal activities such as drug trafficking. Number of

young citizens have become drug abusers and solving the issue of narcotics is a challenge for the law enforcement agencies. According to Maldives Police service records more than 2000 drugs cases are being investigated for past 5 years.12 Country’s porous maritime borders with limited resources to counter drug trafficking situation makes things worse each passing year. In 2006 more than a ton of hash oil, packed and hidden in the lagoon near Dhiffushi Island, in a depth of 30 meters was captured by law enforcement authorities.13 In 2019 in a joint operation conducted by Maldives Police Service and Maldives Coast Guard, a vessel carrying more than 150 kgs of drugs was found at North of Maldives.14

Afghanistan and India’s Andhra Pradesh is notorious for producing hash oil and other types of drugs. In 2019 alone, Maldives Coast Guard has apprehended two Iranian vessels suspected of carrying Drugs.15 Meanwhile India’s Kerala state exercise enforcement squad (SES) reported that drugs transported from Andhra Pradesh to Maldives through Kerala is a new trend that they have observed in the recent past.16 Hindustan Times reported that Maldives is used as a transit destination to carry drugs from Pakistan to India.17

4. The Maritime Security Structures Various Archipelagic States

Every Nation has its own way of formulating and executing measures irrespective of national security or maritime security or any other national matters. It mostly depends on the national interests, economic power, geography, customs and tradition and so on. In this regar, it will be difficult to decide a particular country to follow but certain features can be adapted. Maldives Coast Guard’s former Commandant Col. Mohamed Ibrahim (at present, Commander Central Area) said “Given the context of Archipelago there is no particular archipelagic country’s model that we can follow. Nevertheless thereare certain aspects of security parameters applied in small states that can be applied for Maldives”.18 Following paragraphs we will look into Maldives, Indonesia, Philippines and Mauritius, their philosophy, concepts and their way of doing things with the reference of the literature review.

a. Maldives: Coast Guard is the naval or military arm of MNDF. As the nation’s only maritime force among the four military arms, Coast Guard stands firm and proactive in safeguarding the nation, its people and the legitimate government of the Maldives. To be more precise, the mission of this unique maritime force as stated in Strategic Defence Directive 2012 is to defend the independence, sovereignty and peace of the nation. The MNDF Coast Guard has multiple roles, with the strategic military application settling within the parameters of national defence and territorial integrity as the primary task.19 Towards fulfillment of this huge responsibility, Coast Guard engages in:

- Maritime

- Maritime Mobility and Law

- Maritime Defence and Force

- Disaster Response and

- Maritime Safety and Search and Rescue

- Maritime Pollution and Protection of marine environment.

- Port

- VVIP

b. Indonesia: Indonesia is the largest archipelago in the world, located in a strategic locationat the heart of link between India and Pacific Ocean. Due to this geographic location, imposes an obligation to protect vital sea line of communication (SLOC) and gives the opportunity to access the plenty of marine resources that are there at the disposal of

Figure 3: Comparison between Maldives and Indonesia

Indonesian President in 2014 declared his Global Maritime Fulcrum (GMF) vision to the world. His message was that Indonesia’s livelihood both drives from and depends upon the sea. His vision is to transform its maritime economy and transform Indonesia into a leading maritime power.20

According to assessment conducted by RAND, Indonesia also faced non- traditional threat similar to Maldives which includes, smuggling, IUU fishing, piracy and terrorism. Indonesia has eleven key actors in implementing and executing maritime policies and regulations while Maldives has Maldives Coast Guard as a key player and Marine Police as law enforcement agency along with Coast Guard in territorial water.

Indonesia has Indonesian Water Police (POLAIR) and Directorate of Customs and Excise (BDC) for security and law enforcement, Indonesian Task Force to Combat Illegal Fishing (SATGAS115) to control illegal fishing and protect marine resources Indonesian Search and Rescue Agency (BASARNAS) to formulate and execute search and rescue operations, Directorate General of Sea Transportation to command the Indonesia Sea and Coast Guard, Maritime Security Agency (BAKAMLA) to conduct joint maritime operations at sea and also Indonesian Navy to defend the maritime borders of Indonesia. All these agencies have their independent assets, relevant arms and legal framework to carry out assigned tasks.

Indonesia is planning to build 24 seaports and deep seaports and enhancing the facilities in the existing 5 ports to fill the infrastructure gap. Indonesia is also looking for innovative methods to upgrade their maritime domain awareness in-terms of satellite data which will also cover the vessel monitoring system.21

c. Philippines: Philippines geographically isolated from mainland East Asia, consisting of 7107 islands out of which only 1000 islands are inhabited. Philippines covers coastline of 20107 km. Maritime Security is crucial for Philippines, an archipelagic state in Southeast Asia which has so far struggled to maintain its sovereignty and engaged in disputes at South China Sea. Philippines strategic focus changed from internal disharmony to maritime security when president then Aquino took over in June 2010. President Aquino vowed to modernize the Armed Forces of Philippines and formed the Department of National Defence (DND).

To achieve President Aquino?s vision, Philippines launched a naval build-up program worth USD10 billion for the acquisition within 15 years period. In this project Philippines navy procure six frigates, 12 corvettes, 18 OPVs, 26 naval and multi-purpose helicopters.22 Philippines is a strategic partner of the United Sates in the region since cold war era, besides that Philippines is also part of the Indo-Pacific with United States and Japan.

Figure 4: Comparison between Maldives and Philippines

To counter these threats, Philippine Navy has a functioning fleet of law-enforcement naval assets consisting mostly of fast patrol boats. Philippine Navy also has capabilities, coastal patrol, troop carrying capability and disaster relief assets.23

d. Mauritius: Mauritius and Maldives belongs to two different continents, the former belongs to Africa. These two archipelagic states have common features with respect to maritime environment. Mauritius has a coastline of 330 km with a population of approximately 1.3 million is believed to be one of the countries which will effect most due to global warming and sea level rise.

Figure 5: Comparison between Maldives and Mauritius

Mauritius is facing similar non-traditional maritime threats as of Maldives ranging from Drug trafficking, Piracy, IUU fishing environmental challenges. Maritime Security largely depends on Indian assistance and joint maritime surveillance with India.24

Mauritius has joint military force under the Mauritius Police force which comprising of Anti-Drug Smuggling Unit, Central Investigation Division, and Helicopter Squadron, National Coast Guard, Port Luis North Division, Rodrigues Police, Special Mobile Force, Special Supporting Unit, Traffic Branch and Western Division.25

A conference of ministers on maritime safety and security in 2010 acknowledged, that to tackle the direct and indirect threats in the maritime domain, a comprehensive strategy is essential and should encompass the emerging challenges and threats. In 2019 during the Western Indian Ocean Maritime Security Conference, Minister of Public Infrastructure and Land Transport Mr. Nandhcoomar Bodha stressed the importance of maritime information sharing mechanism between the regional states.26 Understanding the importance of the maritime domain for sustained economic development by Mauritius is the first major step and Initiating the creation of national maritime safety and security strategies by conducting audits of maritime capacities in the operational, financial, legal and regulatory domains could be the second step.27 With these strategic plans and mainly with the assistance of allies Mauritius is moving forward for a safer maritime security environment.

5. Government Strategies – Strengthening Maritime Boundaries of Maldives

In 2018, newly elected Maldivian President Ibrahim Mohamed Solih has stressed the importance of making efficient use of maritime domain on many occasions. He has also stressed the importance of strengthening the maritime security rather investing on land forces. Therefore, development of MNDF Coast Guard becomes his government’s priority. These promises bring hope not only to maritime seafarers but for every citizen of the country since Maldives is a country where every individual is bound to use sea for their lives. In January 2020 during the President’s visit to northern atolls he launched a survey exercise with blue peace prosperity coalition in association with Maldives Marine Research Institute to understand the condition of Maldivian seas which will enable utilization of marine resources in a healthy and environmental friendly manner.28

a. Ruling Party Manifesto: “Jazeeraa Raajje” is the theme given for the Ruling party of Maldives 2018 election’s manifesto. Jazeeraa Raajje which means Archipelagic Maldives or simply the island nation. In its introduction it describes the features of island state, from the natural features to some inherent features of communities living in island states. Then the manifesto covers the theme of “Blue Economy”. Under the blue economy it is mentioned that livelihood of Maldivians and the economy will depend on the environment, protection of sea, lagoons and reefs. Developing and protecting marine resources and fishery industry, development of aqua culture, establishing a sea transport network across the country and tourism.29To execute ruling party’s manifesto, it is common to bring amendments to existing laws and introduce new laws in Maldives.30

b. Changes and Developments within MNDF: When the present government came into power in November 2018, the Commandant Coastguard was not from a maritime background, due to this factCoast Guard faced challenges to implement maritime safety measures and bring necessary changes as per international maritime norms. In July 2019 Chief of Defence force appointed one of the most experienced and knowledgeable maritime officers as Commandant Coast Guard. This positive change brought trust among the sailors and also among civil maritime community of the

c. Maritime Environment – Backbone of Economy: Since the ancient times, the economy of the Maldives depended mainly upon fisheries and other marine resources. As history suggests, these rich marine resources also attracted colonizers towards Maldives. In 1558, when the Portuguese forces raided the capital Male, their focus was to take over the trade of cowries and other artifacts extensively being traded from Maldives.31 Ranked by the United Nations as one of the world’s least developed countries in the early 1990s, Maldives had a GDP based 17 percent on tourism, 15 percent on fishing – which is undergoing further development – and 10 percent on agriculture.32 In a generation, it has gone from being South Asia’s poorest country to the region’s highest per-capita income. Economic growth was powered mainly by tourism, the backbone of the economy, and associated businesses. This section analyses trade and economy of Maldives, new economic aspirations of the government, the security implications of these projects and the envisaged effect on sea power, sustainability, challenges and its protection.

Maldives is ranked 166 among the exporting nations of the world. In 2017, Maldives export figures were $309M and imports costed $1.39B, resulting in a negative trade balance of $1.08B. In 2017 the GDP of Maldives was $4.87B and its GDP per capita was $16.7k.33 The main export of the Maldives remains fish-based products contributing 84.2% of the total exports while top import of the country is petroleum products representing a figure of 47% of the total. The country is increasingly depending on imports due to lack of adequate agricultural activity, fossil fuel resources that match the growing demands and the growth of tourism industry. More than 90% of the overseas and internal trade is through sea routes. The seas, therefore, play a very vital role in the trade and economy of the nation. Maldives is a mixed economy mainly centered on tourism, fisheries and shipping.

d. Fisheries: Fishing provides for a large percentage of Maldivians and has been the oldest form of occupation and practice. Until 1985, it was the largest contributor of Maldivian GDP. Maldivians employ the most sustainable method of pole and line for tuna fishing. Currently, marine capture fisheries account for 9% of GDP, 17% of employment and 66.3% (by value) of the export commodities of Maldives.iii

e. Tourism: Tourism introduced in 1972, the country has experienced a boom as a high-end tourist destination for foreign holiday-makers.34 Today tourism has become the largest revenue generator of the country accounting for 60% of its GDP. Presently 145 resorts, 521 guest houses with more than 45000 beds are there to facilitate tourists and it continues to expand. Maldives is a dream destination with marine ecology and marine environment forming the base of the tourism industry.35

6. Analysis an outcome

Because of ongoing conflicts, economic interests of the world’s major powers deployed their maritime presence in Indian Ocean region. Indian navy’s presence in Mauritius, Madagascar, Seychelles, and Maldives and US presence in Bahrain, and Diego Garcia, Afghanistan with other technical and financial aids to regional archipelagic and small states from their partners Japan and Australia makes the countries in the India Ocean region to remain under their influence. On the other hand, China along with its allies also try to exercise its economic influence.

Non-state actors here are referred to as the non-state maritime actors that pursue political or socio-economic objectives. Having mentioned that only rare cases it would be pure maritime based or land based, its most of the time maritime actors will be operating collaboration of land actors or vice-versa. Modern day pirates operate with modern equipment with the objective of various crimes such as arms robbery, murder, hijacking and many more.

International Maritime Organization annual report 2009 shows that most affected areas include areas where great number of archipelagic states exists, particularly South China Sea, Caribbean and the Indian Ocean. A total of 406 cases of piracy and armed robbery incident cases attempted or occurred in 2009 were reported compared to that of 223 cases reported to IMO in 2018.36

As world population is increasing at a faster pace, marine resources are in decline, challenge and concern for the IUU fishing control is also growing.37 Increasing population will demand to increase food production, to overcome this challenge various conventions and regulations have passed domestically and internationally. UN General Assembly held in 2015 to discuss about the 2030 Sustainable Development Agenda which read “Climate change is one of the greatest challenges of our time and its adverse impacts undermine the ability of all countries to achieve sustainable development. Increases in global temperature, sea-level rise, ocean acidification and other climate change impacts are seriously affecting coastal areas and low-lying coastal countries, including many least developed countries and small island developing States. The survival of many societies, and of the biological support systems of the planet, is at risk”.

7. Regional Responses against Maritime Security Threats

Regional cooperation is essential for developing countries to break the shackles of poverty and underdevelopment. Exchange of expertise and resources can increase the pace of development in comparison to pursuing the goal of economic progress in isolation. European Union (EU) is a role model for all the regional organizations across the world. The cooperation among 6 European countries started in the sector of coal and steel which expedite the rehabilitation of their economic after two world wars. Since then they have come a long way and number of EU countries now have a single currency and the freedom of travel enjoyed by European citizens cannot be witnessed in any other region of the world. Even ASEAN has developed strong cooperation mechanism in order to come up with a joint disaster response. AHA center is established which not only facilitate the synchronization of response across the region but also organize courses for capacity building of member states to enhance their disaster and emergency response capacity.38

Unfortunately, no such collective efforts are to be found at the forum of SAARC. Most of the South Asian countries are either engaged in inter-state conflicts or embroiled in intra-state disputes. This bleak scenario has prevent the region from realizing its true economic potential.39 Maritime is one such domain where this lack of cooperation can be observed, despite facing more or less similar non- traditional maritime security threats. However, south Asian states have adopted some measures and have gone through structural changes individually which can be helpful for Maldives to device their own response mechanism by emulating those practices as per the peculiarities of Maldivian maritime predicament.

Measures taken by the regional and different archipelagic states regarding the improvement development of maritime security are discussed in the subsequent sections.

a. India: Although India and Maldives are incomparable and too different in terms of size, national interests, national objectives, security interests, defense and security capabilities are similar and the country is the closest maritime neighbor and largest trading partner of Maldives. Therefore Maldives is prone to many of the non- traditional security threats that circle around India. In response to sweeping changes in the regional and global geostrategic environment, significant change in India’s security calculus and also because of its national outlook towards seas with maritime security being a vital element of national progress, India had developed a maritime strategy in 2007 and a follow up promulgation titled “Ensuring Secure Seas: Indian Maritime Security Strategy” in October 2015.

India’s maritime development and the vision of leading the Indian Ocean region as a maritime power is becoming more realistic than ever before with the world attention to Indo- Pacific. The phrase “Indo-Pacific” is vibrant for many reasons, ensuring stable balance of power, monitoring and deterring threats from Iran and North Korea, directing various maritime security operations such as counter-terrorist, counter- trafficking and counter-piracy mission.40 Currently India is working in collusion with the United States, Japan, Australia and many other smaller nations. With these developments, India is increasing its maritime presence and surveillance networks which includes the regular maritime surface patrol, Helo operation and Surveillance radar network across the Maldives.

b. Pakistan: Pakistan Maritime Security Agency (PMSA) is primarily responsible for protection of maritime domain in Pakistan from non-traditional maritime security threats. The country has comparable maritime sector and faces challenges of IUU Fishing, poaching by foreign fishing vessels, marine pattern, environmental challenges and illegal trafficking. Maritime Domain Awareness (MDA) has become of paramount significance for Pakistan at national as well as regional level. Therefore, in 2013, Pakistan established Joint Maritime Information Coordination Center (JMICC). The purpose behind establishing such body was to increase coordination among different security agencies by invoking early warning mechanisms in order to tackle any maritime related threats. Five areas come under the scope of JMICC. Those are; Piracy, Maritime Crimes (drug trafficking and human smuggling), Maritime Terrorism, Illegal use of EEZ (fishery crimes, unauthorized resource exploitation), search and rescue (protection of fishermen and helping seafarers in distress). JMICC brings 46 institutions under its ambit for the sake of timely information sharing. Some key institutions include; Naval force, Research Institutes, port authorities, anti-narcotics force and customs. It also regularly engages with the industrial sector and the civil society to ensure the elements of inclusivity and transparency.41 With the growing institutional memory it is evolving in terms of its predictive and analytical capacity. This is essential for Pakistan to become a preventive force rather than engaging merely in rescue and responsive activities.42 Maldives can also follow the suit and establish such inter-organizational coordination at national level may be, body which can ensure early response and preventive capacities to deal with aforementioned maritime security threats.

c. Sri Lanka: Sri Lanka is located in the north-east of Maldives approximately 448 miles away, occupying a strategically important position in the Indian Ocean. It is the second closest neighboring country of Maldives. The waters of the country were heavily infested with terrorist activities of LTTE before they were defeated in 2009. Sri Lanka is facing similar threat as of Maldives after the civil war, such IUU fishing, human and drug trafficking and India-China maritime power 43 Indian Ocean provides a vital sea route linking the Orient and the west. Beside Sri-Lankan Navy, Sri-Lanka is increasing the capability of Sri-Lankan Coast Guard to further strengthening the maritime boarder security as well as maritime law enforcement. Sri-Lanka, Maldives and India have an agreement signed on July 8, 2013 on coordinated handling of maritime security threats such as piracy, gunrunning and terrorism in the Indian Ocean.44

8. Measures taken by Maldives

a. Humanitarian Efforts by MNDF-CG: Maldives has large sea area with limited facilities. Due to the dependence of majority of the population on sea for their livelihoods, they are bound to face weather related challenges. To counter this challenge MNDF-CG have increased their number of search and rescue operations. Following are details of the distress calls received by MNDF-CG and their responses in

| INCIDENT REPORT 2019 – MNDF CG | ||||

|

# |

DETAIL |

TOTAL DISTRESS

CALLS |

ASSISTED (DIRECTLY) | ASSISTED (INDIRECTLY) |

| 1 | Vessel Aground | 225 | 123 | 96 |

| 2 | Engine Breakdown | 318 | 129 | 186 |

| 3 | Accident | 27 | 12 | 15 |

| 4 | Maneuvering Failure | 24 | 12 | 12 |

| 5 | Fire Incidents | 27 | 21 | 12 |

| 6 | Missing person | 33 | 21 | 12 |

| 7 | Diving Accidents | 30 | 24 | 06 |

| 8 | Medical Evacuation | 399 | 399 | 00 |

| 9 | Others | 330 | 240 | 90 |

Table 3: Incident Report 2019 – MNDF CG Info: Maritime Rescue Coordination Center (MRCC), MNDF CG

Due to the peculiarity of Maldivian predicament, the country has to come up with some indigenous measures with incorporation of best models available regionally and globally and are best suited to address the challenges faced by Maldives.

b. Fisheries Act: On 5th September 2019 Fisheries act was passed from the parliament and then ratified by the President Ibrahim Mohamed Solih on 16th September 2019. Following changes observed in the new law with respect to blue economy and maritime security;

- With the introduction of the new Fisheries Act, aqua culture was included, which did not mention and in sustainable aqua culturefishery policy and development is addressed in the objectives of the new law which is not mentioned in the previous law (5/87).

- In objectives of the new law it is asked from concerned authorities to formulate a regulation to prevent IUU

- To reach bilateral agreement with the regional countries to invite foreign investment and also facilitate the Maldivian fishermen to operate without fear in the territorial waters of other countries

- Any sort of net fishing and use of explosives to catch is banned under this Under the new the fishery monitoring, controlling and surveillance authority is given to Maldives Coast Guard, Maldives Police Service and Maldives Customs Service whereas in 5/87 fishery law it is the mandate of MNDF Coast Guard.

9. Conclusion

Increased geopolitical and geostrategic significance of IOR in the recent years have led to the presence of innumerable threats and challenges of maritime dimension in the region. As the third largest oceanic division of the world connecting vital sea lanes east-west carriers containing one-fourth of entire world’s marine cargo and two-thirds of oil. The shift of global focus on the Indian Ocean because of its changing geo-economics and geo-strategy has led to the presence of extra-regional powers in IOR. This change in the new world order has seen an exponential rise of maritime activities with introduction and rise of maritime threats of varying nature. Existence of inter-state and intra-state armed conflicts, poverty, corruption and political instability have also contributed largely to the increasing challenges at sea.

In addition, climate change, IUU fishing, environmental degradation and other non-traditional maritime threats pose great challenges to the region and are affected by all countries in the region. These challenges are more pronounced on small islandnations such as Maldives. As a maritime nation, Maldives has been dependent on its marine environment for growth, sustenance and prosperity since time immemorial. The economy of the country is built on its seas with tourism, fishing and shipping forming the backbone. As Maldives is comprised of more than thousand tiny islands dispersed far and wide with its unique fragile geographic features, effects of climate change and natural disasters are of utmost concern.

Maldivian economy and infrastructure can also be devastated by natural disasters, as the country has experienced during the 2004 Tsunami. Further, the coastal integrity and the national security of Maldives has already been threatened with past incidents of transnational crimes which range from piracy, gunrunning, maritime terrorism, drug trafficking and threats arising from religious extremism. These threats and challenges are likely to grow in the future as Maldives has embarked upon new economic initiatives which include the development of Special Economic Zones (SEZ), expansion of tourism and fisheries sector. The sea power of the Maldives will take a big leap with these aspirations put into action, provided only if commensurate measures are taken to protect the elements of sea power.

Maldives in its security paradigm is unique. Maritime security is the key to ensuring the territorial integrity of the Maldives and is a constituent ingredient of national security. The complexities and uncertainties of our seas persist as the security environment would continue to evolve in view of past and current trends. This would lead to an expansion of Coast Guard’s defence and constabulary role in addressing plausible activities of maritime transnational crimes, resource exploitation and other crimes of maritime nature.

With an overview of the threats and challenges associated with Archipelagic States and Maldives in particular, certain significant strategic objectives for Maldives,can be drawn out for addressing the maritime security in Maldivian waters. The primary objective would certainly be to attain and sustain maritime territorial integrity and sovereignty, security of the islands against all possible non-traditional threats via sea, other maritime economic infrastructure and assure freedom of navigation in accordance with UNCLOS. Secondly, it is important to implement effective conservation, protection and management of the marine environment while implementing measures against effects of climate change.

Asserting effective, sustainable control over fisheries activities, explorationand exploitation of other marine resources in areas within the national jurisdiction is an important objective to promote economic development. A key objective would also be to ensure the integrity of maritime shipping routes throughout Maldivian waters. Enacting new laws, amendment of existing laws to close existing gaps and converge all national efforts/ resources (both public and private) and delineation of roles/ responsibilities of different stakeholders would be absolutely necessary.

The objective of defeating maritime threats and challenges, therefore, need a coherent effort at the national level as well as regional level.. Ensuring the security of own waters is ensuring the security of the region and beyond, because the net security profile of the region or the globe for that matter, is the security of individual countries put together. Maldives, as a maritime nation whose economic well-being and other components of national security is dependent totally on its seas, maritime security must be the top priority. In this regards, some recommendations are appended below:

- Minimize the creation of artificial islands and reduce the usage of one time use plastics for a better maritime environment.

- Expansion of fishing up to EEZ will attract more localized foreign fishing vessels and would generate a better amount of revenue from the fishing industry. This will prompt better regulatory measures dealing with governance, fisheries management, monitoring, control and

- Maldives does not have a strong shipbuilding industry as yet. It can, however be argued that a substantive increase in seaborne trade would lead to development in shipbuilding industry due to the increase in demand for merchant vessels. Shipbuilding industry could go a long way in establishing a robust industry and reduce nation’s dependence on foreign –flagged vessels for

- Regional collaboration should be enhanced amongst all countries for improved maritime management in the region.

- Regional state should work more closely on information sharing & response mechanism

Bibliography

Administrator. “Piracy & Armed Robbery Prone Areas and Warnings?. Accessed 20 January 2020. https://www.icc-ccs.org/ index.php/piracy-reporting-centre/prone-areas-and-warnings.

“Agreement on Port State Measures (PSMA) | Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations”. Accessed 26 December 2019. http://www.fao.org/port-state-measures/en/

“Agriculture, Ministry of Fisheries, Marine Resources and Stakeholder Meetings with the Blue Prosperity Coalition Have Commenced to Discuss the Marine Spatial Planning of the Maldives”. GOV.MV, 12 December 2019. https://www.gov.mv/en/news-and- communications/pr-stakeholder-meetings- with-the-blue-prosperity- coalition-have-commenced-to-discuss-the-marine- spatial-planning- of-the-maldives.

Bateman, Sam. “Maritime Security Governance in the Indian Ocean Region”.Journal of the Indian Ocean Region Vol 12, no.1 (2 January 2016).

Berg, Stephanie. “World Court Weighs Britain’s Claim to Chagos Islands”. Reuters, 3 September 2018. https://www.reuters.com/ article/us-mauritius-britain-worldcourt-idUSKCN1LJ0X0.

Bureau of Crime Records. “Piracy”. Maldive Police Service, 17 February 2020.Stat No:A2(a)2020/051.

Castro, Renato Cruz De. “The Philippines Discovers Its Maritime Domain: The Aquino Administration’s Shift in Strategic Focus from Internal to Maritime Security”. Asian Security vol 12, no. 2 (3 May 2016): 111–31.

Castro, Renato Cruz De. “The Philippines Discovers Its Maritime Domain: The Aquino Administrations Shift in Strategic Focus from Internal to Maritime Security (Asia Security”. Asian Security vol 12, no. 2 (3 May 2016): 111–31

Dinesh C. Sharma. “Climate Change in Our Backyard: Warming of Indian Ocean Threatens Fish Catch”, n.d. www.firstpost.com/ world/climate.

“Doha Declaration on integrating crime prevention and criminal justice into the wider United Nations agenda to address social and economic challenges and to promote the rule of law at the national and international levels, and public participation”.13th UN Congress on Crime Prevention and Criminal Justice, Doha, 12-19 April 2015. https://www.unodc.org/congress/en/previous/previous-13.html

Dr. Teale N. Phelps Bondaroff. “The Illegal Fishing and Organized Crime Nexus:Illegal Fishing as Transnational Organized Crime”, 2015. https://www.unodc.org/documents/congress/background- information/NGO/GIATOC-Blackfish/Fishing_Crime.pdf.

Elleman, Bruce, Andrew Forbes, and David Rosenberg. “Piracy and MaritimeCrime”.The Newport Papers, 1 January 2010. https://digital- commons.usnwc.edu/newport-papers/19.

Fernando, Natasha. “Sri Lanka’s Maritime Security Dilemma”. South Asian Voices, 16 August 2019. https://southasianvoices.org/sri-lanka- maritime-security-dilemma/

General Assembly Welcomes International Court of Justice Opinion on Chagos Archipelago, Adopts Text Calling for Mauritius. ?Complete Decolonization | Meetings Coverage and Press Releases”. Accessed 2 January 2020. https://www.un.org/press/en/2019/ga12146.doc.htm.

Government of Maldives. “General Fisheries Regulation. Attorney General Office,” n.d. www.mvlaw.gov.mv/pdf/gavaid/minFisheries/ 10.pdf).

“Government and Blue Prosperity Coalition Launch Scientific Expeditions to Explore Maldives’ Ocean”. The President’s Office. Accessed 29 January 2020. https://presidency.gov.mv/Press/Article/22935.

IMO. “Reports on Acts of Piracy and Armed Robbery Against Ships”. Annual.London, 2018

Insp LR Rose. “Mauritius Security Force,” 5 November 2019. “Kerala Akee Raajje Ah Drugs Etherekuraa Hub Eh: SEES”. Mihaaru.

Accessed 16 December 2019. https://mihaaru.com/news/59080.

“Maldives History – Early Settlers, Conversion to Islam, Maldivian Heroes, The British Protectorate, Independence”. Accessed 12 October 2019. http://www.vermillionmaldives.com/maldives- history.htm.

“Maldives – HISTORY?. Accessed 23 February 2020. http://countrystudies.us/maldives/1.htm.

Maldives National Defence Force. “Reshaping the Defence Sector for aSecure Maldives”. MNDF, 2012.

Maldives Police Service. “Crime Stats”. Annual. Maldives, 2006. Maldives Democratc Party (Ruling Party). “Manifesto: Jazeeraa

Raajje”, 2018.

Ministry of Environment and Energy. “What You Do for Small Islands, You Do for the World.” 2018. http://www.environment.gov. mv/v2/wp-content/files/publications/20181106-pub-what-you-do- for-small-islands-you- do-for-the-world-2015-2018.pdf.

MNDF CG. “Apprehended Vessels 2019?. Annual, 2019.

Morris, Lyle J., and Giacomo Persi Paoli. “A Preliminary Assessment of Indonesia’s Maritime Security Threats and Capabilities”. Product Page, 2018. https://www.rand.org/pubs/research_reports/ RR2469.html.

“OEC – Maldives (MDV) Exports, Imports, and Trade Partners”. Accessed 23 February 2020. https://oec.world/en/profile/ country/mdv/

“Pakistan in India Ah Drug Fonuvan Raajje Beynunkura Kamah Thuhumathkoffi”. Mihaaru. Accessed 16 December 2019. https://mihaaru.com/news/58023.

Pennink, Bartjan. “The Essence of Research Methodology: A Concise Guide for Master and PhD Students in Management Science”. Accessed 12 October 2019. https://www.academia.edu/32399351/ The_Essence_of_Research_Methodology_A_Concise_Guide_for_Mast er_and_PhD_Students_in_Management_Science.

“Piracy Report Indian Ocean: Maldives, Mauritius, Seychelles”, n.d. https://www.onboardonline.com/industry-article-index/piracy- reports/piracy- report-indian-ocean-maldives-mauritius-seychelles/.

“Raajje Sarahadhdhun 150kg Ge Drugs Athulaigenfi”. Mihaaru.

Accessed 16December 2019. https://mihaaru.com/news/62559. “Regulation on Dangerous Chemical”. Ministry of Defence, 2019.

“Republic of Mauritius- Cooperation and Complementarity among States Keyto Address Maritime Security Issues, Says Minister Bodha?. Accessed 22 December 2019.

Republic of Mauritius. “Embracing a Brighter Future Together as a Nation?, 2019. http://budget.mof.govmu.org/budget2019-20/2019_ 20budgetspeech.pdf.

Research, CNN Editorial. “Mumbai Terror Attacks Fast Facts”. CNN. Accessed 22 October 2019. https://www.cnn.com/2013/09/18/ world/asia/mumbai-terror- attacks/index.html.

Sengupta, Somini. “U.N. Asks International Court to Weigh In on Britain- Mauritius Dispute”. The New York Times, 22 June 201 https://www.nytimes.com/2017/06/22/world/europe/uk-mauritius- chagos- islands.html.

“Sri Lanka and Maritime Security”. Colombo Telegraph, 9 September 2013. https://www.colombotelegraph.com/ index.php/ sri-lanka-and-maritime- security/.

“The Mauritius Police Force – Branches”. Accessed 7 January 2020. http://police.govmu.org/English/Organisation/ Branches/Pages/default.aspx.

“Tourism Industry in Maldives”. Accessed 23 February 2020. https://www.tourism.gov.mv/pubs/TourismIndustryinMaldives/overvi ew.html.

UNODC. “Global Maritime Crime Programme”. Annual Report. United Nations, 2018. https://www.unodc.org/ documents/ Maritime_crime/20190131_-_GMCP_Annual_Report_2018.pdf.

“U.S.?British Deal on Diego Garcia In 66 Confirmed”. The New York Times, 17 October 1975, sec. Archives. https://www.nytimes.com/1975/10/17/archives/usbritish-deal-on- diego-garcia-in-66-confirmed.html.

“What Is IUU Fishing? | Illegal, Unreported and Unregulated (IUU) Fishing | Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations”. Accessed 17 October 2019. http://www.fao.org/iuu-fishing/ background/what-is-iuu- fishing/en/.

Williams, Matt.“What Percent of Earth Is Water?” Accessed 12 December 2019.https://phys.org/news/2014-12-percent-earth.htm

2 “Piracy Report Indian Ocean: Maldives, Mauritius, Seychelles”, n.d. https://www.onboardonline.com/industry-article-index/piracy-reports/piracy-report- indian-ocean-maldives-mauritius-seychelles/.

3 Administrator. “Piracy & Armed Robbery Prone Areas and Warnings?. Accessed 20 January 2020. https://www.icc-ccs.org/index.php/piracy-reporting-centre/prone-areas- and-warnings.

4 Bureau of Crime Records. “Piracy”. Maldive Police Service, 17 February 2020. Stat No:A2(a)2020/051.

5 “What Is IUU Fishing? | Illegal, Unreported and Unregulated (IUU) Fishing | Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations”. Accessed 17 October 2019. http://www.fao.org/iuu-fishing/background/what-is-iuu- fishing/en/.

6 Dr. Teale N. Phelps Bondaroff. “The Illegal Fishing and Organized Crime Nexus:Illegal Fishing as Transnational Organized Crime”, 2015. https://www.unodc.org/documents/ congress/background-information/NGO/GIATOC-Blackfish/Fishing_Crime.pdf. information/NGO/GIATOC-Blackfish/Fishing_Crime.pdf.

7 Ministry of Fisheries Agriculture Marine Resources and, “Stakeholder Meetings with the Blue Prosperity Coalition Have Commenced to Discuss the Marine Spatial Planning of the Maldives”, GOV.MV, 12 December 2019

8Maldives is a country where only pole line, long line fishing are allowed to sustain the fish stock and to protect living resources but IUU fishing is a challenge to achieve desired results. In 2019 alone, more than 20 fishing vessels were captured in the Maldivian territory on the charges of illegal fishing.9

8 Government of Maldives, “General Fisheries Regulation”, Attorney General Office, n.d., www.mvlaw.gov.mv/pdf/gavaid/minFisheries/10.pdf).

9 MNDF CG. “Apprehended Vessels 2019?. Annual, 2019.

10 Dinesh C. Sharma. “Climate Change in Our Backyard: Warming of Indian Ocean Threatens Fish Catch”, n.d. www.firstpost.com/world/climate.

11 Ministry of Environment and Energy. “What You Do for Small Islands, You Do for the World.” 2018. http://www.environment.gov.mv/v2/wp-content/files/publications/2018 1106-pub-what-you-do-for-small-islands-you-do-for-the-world-2015-2018.pdf.

12 Maldives Police Service. “Crime Stats”. Annual. Maldives, 2006.

13 Maldives Police Service. “Crime Stats”. Annual. Maldives, 2006.

14 “Raajje Sarahadhdhun 150kg Ge Drugs Athulaigenfi”, Mihaaru, accessed 16 December 2019, https://mihaaru.com/news/62559

15 MNDF CG. “Apprehended Vessels 2019?. Annual, 2019. MNDF CG, “Apprehended Vessels 2019”.

16 “Kerala Akee Raajje Ah Drugs Etherekuraa Hub Eh: SEES”. Mihaaru. Accessed 16 December 2019. https://mihaaru.com/news/59080.

17 “Pakistan in India Ah Drug Fonuvan Raajje Beynunkura Kamah Thuhumathkoffi”. Mihaaru. Accessed 16 December 2019. https://mihaaru.com/news/58023.

18 Col Mohamed Ibrahim, “Which Archipelagic Sates Maldives to Follow”, 17 December 2019.

19 Maldives National Defence Force, “Reshaping the Defence Sector for a Secure Maldives? (MNDF, 2012).

20 Lyle J. Morris and Giacomo Persi Paoli, “A Preliminary Assessment of Indonesia’s Maritime Security Threats and Capabilities:”. Product Page, (2018), https://www.rand.org/pubs/ research_reports/RR2469.html.

21 Morris and Persi Paoli, “A Preliminary Assessment of Indonesia’s Maritime Security Threats and Capabilities”.

22 Renato Cruz De Castro, “The Philippines Discovers Its Maritime Domain: The Aquino Administration’s Shift in Strategic Focus from Internal to Maritime Security”, Asian Security 12, no. 2 (3 May 2016): 111–31.

23 Castro, Renato Cruz De,”The Philippines Discovers Its Maritime Domain: The Aquino Administrations Shift in Strategic Focus from Internal to Maritime Security” Asia Security Journal, Routledge Taylor and Francis Group, 2016), 05, accessed 22 November 2019.

24 Insp LR Rose, “Mauritius Security Force”, 5 November 2019

25 “The Mauritius Police Force – Branches?, accessed 7 January 2020, http://police.govmu.org/English/Organisation/Branches/Pages/default.aspx.

26 “Republic of Mauritius- Cooperation and Complementarity among States Key to Address Maritime Security Issues, Says Minister Bodha?. Accessed 22 December 2019.

27 Republic of Mauritius. “Embracing a Brighter Future Together as a Nation?, 2019. http://budget.mof.govmu.org/budget2019-20/2019_20budgetspeech.pdf.

28 “Government and Blue Prosperity Coalition Launch Scientific Expeditions to Explore Maldives’Ocean”, The President’s Office accessed 29 January 2020, https://presidency.gov.mv/Press/Article/22935.

29 Maldives Democratc Party (Ruling Party), “Manifesto: Jazeeraa Raajje”, 2018.

30 Government of Maldives. General Fisheries Regulation. Attorney General Office, n.d. www.mvlaw.gov.mv/pdf/gavaid/minFisheries/10.pdf).

31 “Maldives – HISTORY?. Accessed 23 February 2020. http://countrystudies.us/ maldives/1.htm.

32 Ibid.

33 “OEC – Maldives (MDV) Exports, Imports, and Trade Partners”. Accessed 23 February 2020. https://oec.world/en/profile/country/mdv/

34 “Tourism Industry in Maldives”, accessed 23 February 2020, https://www.tourism.gov.mv/ pubs/TourismIndustryinMaldives/overview.htm.

35 “Maldives to Open 20 New Resorts in 2019”, Maldives Insider, 10 February 2019, https://maldives.net.mv/29628/maldives-to-open-20-new-resorts-in-2019/.

36 IMO, “Reports on Acts of Piracy and Armed Robbery Against Ships”, Annual (London, 2018 2009).

37 Leo J. Bouchez, “The Future of the Law of the Sea: Proceedings of the Symposium on the Future of the Sea Organized at Den Helder by the Royal Netherlands Naval College and the International Law Institute of Utrecht State University 26 and 27 June 1972” (Springer, 2013).

38 Petz, Daniel. “Strengthening egional and national capacity for disaster risk management: the case of ASEAN” Brookings-LSE Project on Internal Displacement 14 (2014)

39 Dubey, Muchkund, “SAARC and South Asian economic integration”. Economic and Political Weekly (2007) 1238-1240

40 David Michel and Ricky Passarelli, “Sea Change, Evolving Maritime Geopolitics in the Indo- Pacific Region” (Sitmon, 2014), https://www.stimson.org/wp-content/files/file- attachments/SEA-CHANGE- WEB.pdf.

44 Naghmana Zafar, “Building Maritime Security in Pakistan – The Navy Vanguard,” in Capacity Building for Maritime Security, ed. Christian Bueger, Timothy Edmunds, and Robert McCabe (Cham, Switzerland: Springer International Publishing, 2021)

41 Baber Ali Bhatti. “Joint Maritime Information Coordination Center: A milestone toward Maritime Domain Awareness in Pakistan” see at : https://www.maritimestudy forum.org/joint-maritime-information-coordination-center-a-milestone-toward-maritime- domain-awareness-in-pakistan/

42 Malik, Hasan Yaser. “Role of Pakistan Navy in Indian Ocean Blue Diplomacy.” Defence Journal 21.8 (2018): 33-25

43 “Sri Lanka’s Maritime Security Dilemma”, South Asian Voices, 16 August 2019, https://southasianvoices.org/sri-lanka-maritime-security-dilemma/.

44 “Sri Lanka And Maritime Security”, Colombo Telegraph, 9 September 2013, https://www.colombotelegraph.com/index.php/sri-lanka-and-maritime-security/.

The US Free and Open Indo-Pacific Strategy: Implications for China (2017-present)

Maheera Munir, Aiysha Safdar

Abstract

The Indo-Pacific region is becoming the focal point of strategic competition in the 21st century. The region, previously limited to the Asia-Pacific, has evolved into a wider geographical and geopolitical realm, thanks to the unparalleled economic, political, military, and diplomatic growth of China over the past three decades. Since 2006-07, the region is receiving wider attention from the United States and its regional allies – Japan, Australia, and India. While the term Indo-Pacific has been developing into a geopolitical discourse since then, it came to the surface in the United States in 2017 as Trump administration assumed power. The United States views the rise of China as a threat to its liberal rules-based order and global hegemony. This article deals with the US Free and Open Indo-Pacific Strategy (FOIP) formulated by Trump administration in November 2017 and reformulated by Biden administration in February 2021 to counter growing China’s assertiveness in the region, which China calls its ‘peaceful rise’. To achieve its goals, the United States heavily relies on its strategic partners, each of which has a different interpretation of the Indo-Pacific. Ineffectiveness of various bilateral and multilateral engagements along with the implemental limitations of the Indo-Pacific strategy itself has, so far, failed to bring negative implications for China. This puts the future regional order of the Indo-Pacific in a jeopardy. The regional actors are not willing to become a tool of the US or China in balancing each other’s threats indirectly. This leaves us to assuming that the Indo-Pacific region is most likely to observe a multilateral order in years to come. Given the criticalness of the situation, both the United States and China should opt for a cooperation mechanism rather than containment strategies to ensure peace and stability in the Indo-Pacific.

Keywords: Asia-Pacific, Free and Open Indo-Pacific, United States, China, QUAD, Regional Order, Maritime Cooperation

*Maheera Munir is a post-graduate student in the Department of International Relations, Kinnaird College for Women Lahore.

**Dr. Aiysha Safdar is PhD in International Relation & Head of Department in the Department of International Relations, Kinnaird College for Women Lahore.

- Introduction

As the world order changed after collapse of USSR in 1991, the US has been enjoying its position as the global hegemon. Only a decade later, China grew to be the second largest economic power in 1999. Today, China has its foothold in every region around the world. It has been doing great in maintaining diplomatic ties, security alliances and economic investments. These rapid economic, political and security achievements of China are putting US in a difficult position as the hegemon. As the world has moved from traditional means of warfare to non-conventional approaches like economic and cyber warfare, US has been adopting strategic measures to counter China’s growing power and threat in Indo-Pacific region and across the globe.

With increasing globalization, interdependence and modern security trends, it became important to balance the threat rather than balance the power. The balance of power theory suggests that states ensure and protect their survival through military power and resources only. However, Stephen Walt put forward the concept of balance of threat in 1987 stating that states try to increase their capabilities based on the perceived threats instead of power the other state holds. While balance of power resorts only to military aspect, balance of threat encompasses all the domains including economic, political, and non-conventional, all of which add to the resources of a state. As the aggregate power of China increased, its military power enhanced and it became capable of acting offensively due to exponential growth in its naval power, the US perceived security threats from China in all the domains be it politics, economy, or military.

Ever since, it has been shaping strategies to balance China’s threat such as A Cooperative Strategy for 21st century Seapower (CS21) formulated by US in 2007, the Defense and Strategic Guide 2011, the Asia pivot strategy 2012 which mentioned India as the ‘regional anchor’ and ‘broad security provider for Indian Ocean Region’ and A Cooperative Strategy for 21st Century Seapower Forward Engaged Ready (CS21R) in 2015 that put forward American concerns regarding increasing China’s assertiveness. As Chinese threats to India increased and needs for US strategic cooperation enhanced, India revised its maritime doctrine in 2015 to broaden its area of security interest from Horn of Africa to Western Pacific. Through China’s Anti-Access and Anti-Denial strategy (A2/AD) in the South China Sea, China has projected the possible expansion of its sea denial rhetoric to the Indo-Pacific in order to protect its sea lanes of communication (SLOCs). With the Trump administration in power since 2017, the threat of China’s power is being taken more seriously. The 2017 National Security Strategy (NSS) and 2018 National Defense Strategy (NDS) descripted China as a strategic competitor and a revisionist power. The most recent US strategy to counter China’s influence is Free and Open Indo-Pacific strategy (FOIP) that covers Mekong states and Pacific Island states as well as South Asia.

Through its Indo-Pacific strategy, US has been trying to curb China’s growing influence. So far, China has responded to the strategy diplomatically under its Peaceful Coexistence foreign policy and has followed its principles of mutual respect, mutual non-aggression, mutual non-interference, and mutual benefits. This study seeks to investigate the transformation of strategic thinking that changed Asia-Pacific into a broader and more significant region, the Indo-Pacific. Next, it addresses the underlying aims of US behind the Free and Open Indo-Pacific (FOIP) strategy. It examines the credibility and effectiveness of bilateral and multilateral engagements in the Indo-Pacific under FOIP to counter China’s growing power. It further analyses economic, political and security implications for China under US Indo-Pacific strategy as well as how the current rules-based regional order is more likely to change into a multipolar order. Lastly, it evaluates how far US has been successful in containing China’s rise.

- Transformation of Strategic Thinking: From Asia-Pacific to Indo-Pacific

The concept of Indo-Pacific came forward as a progress in the traditional ‘Asia-Pacific’ approach which solely focused on United States and its East Asian allies in the region – Australia, Japan, Taiwan, South Korea, and Vietnam. However, with the economic and political advancements, the center of gravity has extended to the West. The region includes nine out of the ten busiest seaports of the world are in Indo-Pacific region. This accounts for approximately 60% of the global maritime trade through Asian region, with South China Sea alone acting as the transit for one-third of the global shipping.[1] The emergence of new economic and political actors (China, India, and Asian Tigers) along with the changing trends in the international political economy, the entire region from Horn of Africa to Western Pacific has evolved to be of great strategic significance.

It all began in 2006-07 when Japanese Prime Minister Shinzo Abe delivered a speech in the Indian parliament on the “Confluence of the two seas”. He emphasized on the increasing politico-economic connectivity and interdependence between the two oceans, calling the Pacific Ocean and the Indian Ocean as a single space. However, the idea came to the surface again in 2011 when US Secretary of State Hillary Clinton used the term Indo-Pacific while speaking to the public of how US is pivot to Asia. For the first time, the term Indo-Pacific officially appeared neither in Japan nor US but Australia’s white paper Australia in the Asian century in 2012. With increasing regional focus of the term, India also contributed to Indo-Pacific discourse by including the term in its 2015 maritime strategy Ensuring Secure Seas: Indian Maritime Security Strategy.[2]

However, Indo-Pacific made it to the foreign policy discourse for the very first time in 2016 as Japan announced its Free and Open Indo-Pacific Strategy at the Tokyo International Conference on African Development, later persistently discussed at IISS Shangri-la Dialogue as an attempt to counter Chinese power and influence in the region. During his address at APEC summit in November 2017, President Trump mentioned “Free and Open Indo-Pacific” as the focal element of US policy towards Asia. The very next month, in December 2017, the United States released its National Security Strategy, documenting the term Indo-Pacific officially for the very first time, thus bringing the Indo-Pacific into a true geopolitical context.[3] QUAD, re-established after negotiations in November 2017 that brought regional democracies, Japan, Australia, and India together with U.S. and later the AUKUS alliance under President Biden highlight the continued strategic efforts towards Chinese containment in the Indo-Pacific.

The transformation over strategic thinking has directed geopolitical focus towards the Indo-Pacific but the Chinese officials have been quite passive in response to the use of this term by the United States and its regional allies. As early as 2018, the foreign minister of China Wang Yi rejected the notion of the Indo-Pacific, calling it merely an idea to grab popular attention.[4] Chinese scholars and officials have repeatedly regarded the idea as United States’ attempt to establish a grand alliance in the Indo-Pacific region, use India as a tool to balance Chinese threat, declare cold war in a new style, or simply find a better cooperative space between United States and China. However, with the strengthening geopolitical context of the term, Chinese thinktanks are now working on developing a refined perspective towards Indo-Pacific. Having played the most crucial role in making Indo-Pacific region the strategic centre of gravity, it is impossible for China to ignore the regional developments taking place over the Indo-Pacific idea.[5]

- Theoretical Framework: Balance of Threat

Stephen M. Walt developed a countertheory to Balance of Power known as the Balance of Threat in his work Origin of Alliances (1987) as he asserted that states react to threats, not to power. So, states tend to form alliances or coalitions against a rising state that threatens their national interests and sovereignty. Balancing means that states tend to ally against a potential hegemon before it becomes too strong to ensure their survival. So, as a safe strategy, it is better to align with the likeminded states that are perceiving similar kinds of threats. The alternative to balancing act is band wagoning under which states ally with the rising threat rather than against it in order to protect their interests and ensure their survival. However, as per Walt, states are more likely to balance rather than bandwagon because of the changing intentions and unreliable perceptions.[6] The bigger the perceived threat, the bigger is the need to balance it. Four elements, according to Walt, define perceived threats:

i. Aggregate power (how powerful the threatening state is, in terms of size, population, economic capabilities and latent power)

ii. Geographical proximity (how close is it)

ii. Offensive capabilities (the extent of its military might)

iv. Offensive intentions (the extent of its aggressive actions)

The aggregate power is the overall power that a state can wield and due to the threat, this power may become a motive for either balancing or band wagoning. If states are threatened from a proximate power in a regional framework, they will align in response to those threats. If a state has a large offensive capability, they often provoke an alliance rather than those who are capable of only defending. States may balance this threat by allying with others or may also be forced to bandwagon because one’s allies may not be able to provide assistance quickly enough and hence for the vulnerable states, there is little hope in resisting. If states appear aggressive, they provoke a balancing action by other states. China’s rise in the international system as a whole is economically driven and US is balancing the threat both internally and externally.

Internally, through building its own military strength

Externally, through its allies and partners

The four elements of threat perception put forward by Walt have made regional actors like India and Japan more threatened by Chinese power than the US power in the Indo-Pacific. This mutual concern for the threat posed by China has cultivated in the form of the US Indo-Pacific strategy, its formal alliances, and implicit strategic partnerships, all to contain and balance the Chinese threat. John Mearsheimer took this very balancing theory into account when he said that ‘most of Beijing’s neighbours will join the US to contain Chinese power’.[7]

- Credibility and Implications of the Free and Open Indo-Pacific Strategy (FOIP) for China

The United States sees China’s economic and military actions and assertiveness as a threat to the liberal rules-based order in the Indo-Pacific. United States is under the perception that increased China’s foothold will constraint US’ role as the global hegemon. The 2017 US National Security Strategy and the 2018 National Defense Strategy put special emphasis on the Indo-Pacific region, calling China a revisionist power and stressing upon the need to limit Chinese expansionism and assertiveness. Both these strategies called for a specific US policy for the Indo-Pacific region to deter Chinese aggression. Thus, came forward US Free and Open Indo-Pacific Strategy (FOIP). In order to achieve the Indo-Pacific agenda, the US has relied on two key tools: bilateral relationship and multilateral engagements across military, political, economic, and diplomatic domains.

a. Bilateral Relationships: United States has further narrowed down its relationships to bilateral level in order to develop closer cooperation with the significant regional actors. This includes the 5 most crucial allies – Japan, Australia, India, South Korea, and Taiwan. Over the years, United States have had a number of bilateral deals and partnerships with Japan. The recent ones to strengthen the initiative of Indo-Pacific strategy are Strategic Energy Partnership and Strategic Digital Economy Partnership, extending from Indo-Pacific to Africa.

Other than that, US is largely focusing on growing its partnership with India. Under 2+2 Dialogue in 2018, US and India have strengthened their defense and economic ties. India also purchased $16 billion worth of defense weapons and $6.2 billion of mineral fuel products to secure US India Strategic Energy Partnership. Interestingly, US and India have also signed a $1.5 billion project for development of Earth observation satellite, NISAR.[8]

b. Multilateral Engagements: While ASEAN, Lower Mekong Initiative and Asia-Pacific Economic Cooperation (APEC) are popular multilateral engagements of US, the Trilateral Strategic Dialogue – US, Japan, and Australia – has always been a crucial nexus in the Indo-Pacific. So far, this multilateral initiative has received highest attention from US, Japan, and Australia. Each state has its own points of conflict and threat perceptions when it comes to China. While there are some diverging interests, the element of countering China alone has proved to be enough in bringing these actors to the table. Interestingly, India has also become a part of this strategic dialogue and its involvements in various meetings throughout 2018 and 2019 resulted in Quadrilateral Strategic Dialogue, commonly known as the Quad Alliance.[9]

c. Credibility of the QUAD Alliance: While Quad is seen as a security alliance to further strategic interests of four partners in the region as an attempt to balance Chinese threat and bring success to FOIP, there are many limitations to the Quad initiative due to differences in the Indo-Pacific ideology of each actor. These differences occur due to: